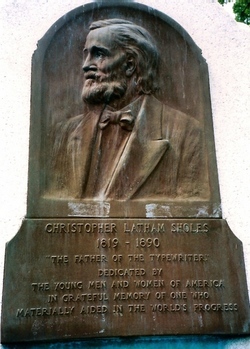

Christopher Latham Sholes was born February 14, 1819 in Mooresburg, Pennsylvania.

As a teenage, Sholes worked as an apprentice printer.

In 1837, Sholes moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin were he took a job at a local newspaper.

By 1845, Sholes had become editor of the Southport Telegraph, a small newspaper in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

In 1848, Sholes was elected to the Wisconsin State Senate where he served a one year term. He also served on the Wisconsin State Assembly from 1852-1853, and again on the Wisconsin Senate from 1856-1857.

Numbering Machine

Following a strike by compositors of his printing press early in 1866, Sholes unsuccessfully tried to build a machine for typesetting.

Typewriters had been invented as early as 1714 by Henry Mill and reinvented in various forms throughout the 1800s. It would be Sholes, however, who invented the first one to become commercially successful.

Sholes arrived at his typewriter through a different route. His initial goal was to create a machine to number pages of a book, tickets, and so on.

Working with Samuel W. Soule, Sholes and Soule developed their numbering machine at Kleinsteubers machine shop in Milwaukee.

Together, they patented it November 3, 1866.

Kleinsteuber’s Machine Shop, Milwaukee, where Christopher Latham Sholes’ first typewriter was manufactured.

Then, lawyer and amateur inventor Carlos Glidden, asked Sholes if the Sholes and Soule Numbering machine could be modified to produce letters and words as well.

Further inspiration came in July 1867, when Sholes read an article in Scientific American describing the “Pterotype,” a prototype typewriter that had been invented by John Pratt. From the articles description, Sholes decided that the Pterotype was too complex and set out to make his own machine.

Typewriter

For this project, Sholes enlisted the help of Soule once more, as well as Carlos Glidden who became the partner that provided the funds.

The July 1867 Scientific American unillustrated article had figuratively used the phrase “literary piano.”

So Sholes developed a model that had a keyboard literally resembling a piano.

The machine had black keys and white keys, laid out in two rows.

It did not contain keys for the numerals 0 or 1 because Sholes felt the letters O and I were sufficient:

3 5 7 9 N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

2 4 6 8 . A B C D E F G H I J K L M

the first row keys were made of ivory and the second row of keys were made of ebony, and the rest of the machine framework was made out of wood. They named their new machine from another article that they had read about a typewriting machine, thus their “typewriter.”

It was in this form that Sholes, Glidden and Soule were granted patents for their invention on June 23, 1868 and July 14, 1868.

The first document to be produced on their typewriter was a contract that Sholes had written, in his capacity as Comptroller for the city of Milwaukee.

Machines similar to Sholes’s had been previously used by the blind for embossing, but by this time inked ribbon had been invented, which had made typewriting in its current form possible.

At this stage, the Sholes-Glidden-Soule typewriter was only one among dozens of similar inventions.

They wrote hundreds of letters on their machine to various people, one of whom was James Densmore of Meadville, Pennsylvania. Densmore foresaw that the typewriter would be highly profitable, and offered to buy a share of the patent, without even having laid eyes on the machine.

The trio immediately sold Densmore one-fourth of the patent in return for his paying all their expenses thus far.

When Densmore eventually examined the machine in March, he declared that it was good for nothing in its current form, and urged them to start improving it.

Discouraged, Soule and Glidden left the project, leaving Sholes and Densmore in sole possession of the patent.

Realizing that stenographers would be among the first and most important users of the machine, and therefore best in a position to judge its suitability, they sent experimental versions to a few stenographers.

The most important of them was James O. Clephane, of Washington D.C., who was in the process of trying out all of the various typeset machines, subjecting them to such unsparing tests that he destroyed them, one after another, as fast as they could be made and sent to him.

Clephane’s judgment of Sholes’ typewriter was similarly caustic, causing Sholes to lose his patience and temper.

But Densmore insisted that this was exactly what they needed:

“This candid fault-finding is just what we need. We had better have it now than after we begin manufacturing. Where Clephane points out a weak lever or rod let us make it strong. Where a spacer or an inker works stiffly, let us make it work smoothly. Then, depend upon Clephane for all the praise we deserve.”

Sholes accepted this advice and set out to improve his typewriter machine at every iteration, until they were satisfied that Clephane had taught them everything he could.

Sholes typewriter, 1873. Museum, Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society.

By this time, they had manufactured 50 machines or so, at an average cost of $250. They decided to have the machine examined by an expert mechanic, who directed them to E. Remington and Sons (which later became the Remington Arms Company), manufacturers of firearms, sewing machines, and farm tools.

In early 1873 they approached Remington, who decided to buy the patent from them. Sholes sold his half for $12,000, while Densmore, still a stronger believer in the machine, insisted on a royalty, which would eventually fetch him $1.5 million.

Sholes returned to Milwaukee and continued to work on new improvements for the typewriter throughout the 1870s, which included the QWERTY keyboard.

QWERTY

James Densmore had suggested splitting up commonly used letter combinations in order to solve a jamming problem caused by the slow method of recovering from a keystroke: weights, not springs, returned all parts to the “rest” position.

Sholes solution was to place commonly used letter-pairs (like “th” or “st”) so that their typebars were not neighboring, avoiding jams.

Sholes struggled for the next five years to perfect his keyboard, making many trial-and-error rearrangements of the original machine’s alphabetical key arrangement.

The study of letter-pair frequency by educator Amos Densmore, brother of the financial backer James Densmore, is believed to have influenced the arrangement of letters, but was later called into question.

The name comes from the first six keys appearing on the top left letter row of Sholes’ keyboard.

Latham Sholes’s 1878 QWERTY keyboard layout

Although QWERTY today is considered to slow down typists, it was originally designed to speed up typing by preventing jams.

Every word in the English language contains at least one vowel, but on the QWERTY keyboard only the letter “A” is located on the home row, which requires the typist’s fingers to leave the home row for most words.

This QWERTY layout is still used today on both typewriters and English language computer keyboards, although the jamming problem no longer exists.

Christopher Sholes died on February 17, 1890 after battling tuberculosis for nine years, and is buried at Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee.

Now WE know em